Tango is not just a fascinating dance—it is a rich philosophy, culture, and way of life. The search of tango is the search of connection, love, fellowship, unity, harmony, and beauty—an idealism that is not consistent with the dehumanizing reality of the modern world. The world divides us into individuals, but tango brings us together as a team and community. In tango we are not individualists, feminists, nationalists, Democrats, or Republicans—we are simply human, intertwined and interdependent. Tango invites us to tear down walls, build bridges, and rediscover our shared humanity through connection, cooperation, accommodation, and compromise. It is a dance that reminds the world how to love.

November 18, 2021

Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and Chinese-Style Modernization

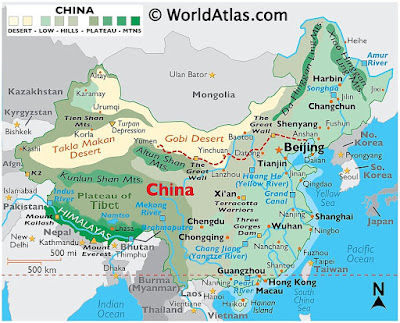

Five thousand years ago, tribal alliances and city-states emerged in the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of East Asia. Over time, these civilizations coalesced into a single entity—China—which expanded steadily until it met formidable natural barriers on all sides. To the northeast lay the icy expanse of Siberia; to the north, the vast, desolate Mongolian deserts. The west was dominated by towering mountain ranges, with peaks exceeding 5,000 meters, including the Himalayas, home to Mount Everest at 8,848 meters. The southwest featured the rugged Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and dense tropical jungles, while the southeast and east faced the immense Pacific Ocean. In ancient times, lacking modern transportation, these geographical obstacles were virtually insurmountable, effectively isolating China from the outside world. Shielded by these natural defenses, the Yellow and Yangtze River basins enjoyed a temperate climate and abundant rainfall brought by the Pacific monsoon, making them ideal for agriculture. This unique geographical setting played a decisive role in shaping the development and character of Chinese civilization.

China was able to develop its unique and remarkable culture largely due to geographical barriers that limited outside influence and prevented foreign aggression. This allowed China to remain the only ancient civilization to develop without interruption for over five millennia. Yet they also limited the Chinese worldview. Enclosed by these barriers, the Chinese believed their land constituted the main body of the world—which they called 天下 (tianxia), literally, “all under heaven.” The Yellow River and Yangtze River basins lay at its center, thus, China was named 中國 (zhongguo), meaning “central country.” Blessed with fertile lands and abundant resources, China was far more prosperous than the surrounding frontier regions. Chinese peasants, living in kinship-based villages, grew deeply attached to their fertile farm land and were uninterested in the barren territories beyond, fostering a reserved and inward-looking temperament. Rather than expanding militarily, the Chinese built the Great Wall to protect themselves from northern nomads. This 21,000-kilometer Wall, located along the 400 mm isoprecipitation line and spanning from east to west, symbolized the divide between sedentary agricultural societies and nomadic cultures. Nomadic tribes who crossed the Wall and settled in China were eventually assimilated into Chinese farming culture, becoming Chinese themselves. Thus, Chinese civilization, shaped by its geography, epitomized the triumph of a settled, productive way of life over a nomadic, predatory one. The Chinese have long taken pride in their land, culture, and lifestyle, as China has been the world’s most advanced civilization until the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

This geographical seclusion also fostered a monistic rather than pluralistic vision of the world. Unlike the Western notion of a world composed of many sovereign states, the ancient Chinese viewed the world as an integrated whole, with China as its sole civilized center. This worldview made the concept of 大一統 (great unity) a core element of Chinese cultural identity. Surrounding ethnic tribes were regarded as vassals within the Chinese tributary system, many of which were gradually sinicized and incorporated into China.

Scholars have noted that China’s agrarian lifestyle required the sharing of water resources and necessitated large‑scale, coordinated irrigation and water management across different regions, contributing to the rise of a centralized state that emphasizes national unity and cooperation (see Understanding China: Yellow River and the Character of the Chinese Nation). Throughout its history, China has experienced the rise and fall of numerous dynasties, yet each cycle ultimately ended in reunification rather than permanent fragmentation (see Understanding China: The Vicious Circle of Regime Change).

The first unification occurred in 221 BC, when the state of Qin (pronounced “chin,” from which “China” is derived) defeated all rival states and established a unified dynasty. Qin standardized laws, scripts, currency, weights, measures, and even vehicle tracks, abolishing feudal fiefdoms in favor of a system of prefectures and counties. This system laid the foundation for China’s enduring stability and prosperity and was adopted by all subsequent dynasties. The development of the Chinese political system and culture has shown a remarkable capacity for assimilation and integration, inspiring neighboring states to emulate it. Throughout history, many ethnic groups that partially or entirely conquered China were eventually absorbed into Chinese culture. This process of sinicization, rather than military expansion, accounts for the vast extent of China’s territory.

Aligned with this monistic worldview, Confucianism promotes a vision of society as an integrated whole. The 大同 (datong) society, an ideal described in Confucian classics, imagines a harmonious world where the wise govern, the honest live peacefully, the vulnerable are protected, and crime is nonexistent. Contrast sharply with Western individualism, which emphasizes personal interests and often pits the strong against the weak, causing individuals to be egocentric and belligerent, Confucianism envisions society as an extended family, where members cooperate, seek common ground, prioritize communal interests over personal ones, and work together as a team. In Confucianism, individuals are not viewed as isolated and autonomous but as integral members of society, born into specific relationships with defined roles and responsibilities. They adhere to etiquettes designed to maintain social harmony—akin to tango dancers observing milonga codes in the milongas. These etiquettes or proprieties were practiced even before Confucius’s time, by the people of the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th–8th century BC). Confucius (551 BC–479 BC) and his disciples were scholars and ardent advocates of these ancient rites. In essence, Confucianism is rooted in a tradition that remains central to Chinese culture.

This tradition emphasizes the importance of harmonious relationships among people and society as a whole. Confucianism holds that societal stability depends on a solid foundation: the people. A ruler, like the head of a family, derives authority from the people and is responsible for their welfare. As Confucius said, “The ruler is the boat; the people are the water. Water can carry the boat, or overturn it.” Mencius (372 BC–289 BC), another prominent Confucian sage, similarly underscored the central role of the people, asserting that they are the most important, followed by the state, with the monarch being the least. Confucianism teaches that a ruler’s legitimacy stems from the support or mandate of the people, and an unrighteous ruler will lose that mandate. In essence, Confucianism represents a people-centered collectivist humanism, in contrast to the individualistic humanism of the West. This collectivist humanism has shaped Chinese governance ideals that continue to this day—from Confucius's "天下為为公" (the world belongs to all people), to Sun Yat-sen's "Three Principles of the People," to the founding of the People's Republic of China, to the CCP's mission of serving the people, to Xi Jinping's call for a community with a shared future for mankind. (See Democracy vs. Plutocracy.)

Rooted in this people-centered collectivist humanism, Confucianism advocates for benevolent governance. Confucius believed that benevolence (仁) is the essence of human nature, distinguishing humans from other animals. When a student asked him what the meaning of benevolence was, Confucius replied, "To love others." Unlike Machiavelli, who separated morality from politics, Confucius saw morality as the cornerstone of governance. A ruler must be a saint at heart, a moral leader, and a role model. Only through self-cultivation can he manage his family, govern his country, and bring peace to the world. Confucius emphasized the importance of proprieties (禮), but he stressed that rule observances must be grounded in benevolence, or they become hollow gestures. His followers, however, divided into two camps. The school that prioritized benevolence was later recognized as the orthodoxy of Confucianism. The school that emphasized proprieties evolved into Legalism. The unification of China by the Qin state in 221 BC was achieved through the use of military power and severe penal laws under the influence of the Legalist school of thought. Due to its brutality, the Qin Dynasty survived with only two rulers before it was overthrown by widespread rebellions. Learned from this lesson, in 134 BC, Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty accepted the advice of a Confucian scholar, Dong Zhongshu (179 BC–104 BC), to replace other schools of thought with Confucianism and to implement benevolent rule. Since then, Confucianism has become the official ideology of China. Unlike Christianity and Machiavellianism, which assert that human nature is inherently evil, Confucianism holds that human nature is inherently good, therefore opposes the Legalist reliance on strict laws and harsh punishments as primary tools of governance, instead advocates for rule through virtue and education. This approach gave rise to the Chinese tradition of prioritizing morality and learning.

In 587 AD, Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty established the imperial examination system, linking education with civil service. This meritocratic system played a pivotal role in shaping China's effective political bureaucracy. It further solidified the status of Confucianism, promoted Confucian learning, opened the way for talented individuals from all walks of life to enter politics, and gave rise to the scholar-official class. China's modern civil servant selection system is a continuation of this legacy. Many researchers argue that, compared to Western electoral democracy, China’s meritocratic system is better equipped to produce leaders with moral integrity, practical knowledge, and strong abilities, as evidenced by China's illustrious history and modern economic achievements. However, in the past, the imperial examination system failed to prevent the recurrence of dynastic cycles. Today, China seeks to address this through political reforms, such as collective decision-making, age and term limits for officials, clean government initiatives, self-correction mechanisms, disciplinary inspection, anti-corruption campaigns, public supervision of the government, reporting and petitioning systems, and impeachment procedures. These efforts aim to improve governance, ensure accountability, and prevent the emergence of autocracy.

Also based on this people-centered collectivist humanism, Confucianism calls for the equitable distribution of wealth and condemns prioritizing economic interests over morality, using unethical means to accumulate wealth, competing for monetary gain, and widening the gap between rich and poor. Confucians argued that the ruler should disperse the nation's wealth among the people rather than competing with the people for profit. As Confucius said, “Rulers should not worry about not having enough, but about inequality.” This ethos inspired Chinese rulers throughout ages to adopt egalitarian policies and implement benevolent governance. However, the emphasis on morality over economy historically led to the devaluation of merchants in traditional Chinese society, where they ranked below scholars, farmers, and craftsmen. China's early post-1949 policies reflected this Confucian tendency, prioritizing morality and scholarship over economic development. During the reform and opening-up era initiated by Deng Xiaoping, however, the government shifted policy to encourage business and entrepreneurship. Subsequently, the Chinese government targeted poverty alleviation programs and anti-monopoly efforts, upholding Confucian egalitarianism while recognizing the importance of economic development as a means to achieve common prosperity. The Confucian emphasis on production over commerce has also contributed to China’s physiocratic tradition, favoring agriculture and manufacturing over speculative capitalism, which often leads to cyclical recession, economic hollowing, corruption, inequality, and systemic collapse (see Mammonism).

Another Confucian concept with profound and far-reaching influence is the Doctrine of the Mean, which advocates moderation and harmony. Confucius believed that harmony is the fundamental law of nature, and that moderation leads to harmony while excess leads to disharmony. He regarded humility, politeness, impartiality, and the avoidance of extremes as the essential qualities of a 君子—a person of high moral character. Deviation from the Doctrine of the Mean, he warned, could lead to disastrous consequences (see Meeting in the Middle). This Confucian proposition is incompatible with Western liberalism and individualism. Chinese people lack the arrogant, bigoted, extreme, domineering and aggressive spirit of many Westerners, Confucianism is the main reason. This emphasis on moderation, balance and harmony has discouraged the Chinese from engaging in Western-style partisan politics, which tend to create division, conflict, hostility, and polarity. While Western culture prioritizes individualism, partisanship, and competition, Chinese culture values collectivism, unity, and cooperation. The Chinese tend to approach issues in a holistic, comprehensive, and balanced manner. Today's Chinese leadership is acutely aware that both morality and personal freedom are important and an excessive focus on either one can be harmful. Overemphasis on morality can suppress initiative and creativity, while overemphasis on individual liberty can exacerbate conflict and inequality. Striking a balance, however, is no easy task. Historically, Confucian morality was transformed by Neo-Confucianists into a rigid ideology that restricted personal freedom. Western liberalism and individualism represent the opposite extreme. The Chinese now strive to find a balance that aims at a society respecting both individual freedom and social morality (see Pluralism vs. Monism).

The peaceful life of the Chinese has finally come to an end. In 1840, Western powers used opium, warships and cannons to finally bombard China's door open, forcing the Qing Dynesty (1644-1911), the last Chinese dynesty, to sign a series of unequal treaties for ceding territories and indemnities. Confronted with this humiliating defeat and the stark disparity between an agricultural China and the already industrialized West, the Chinese began seeking ways to save their country. Over the eight decades following the Opium War, they attempted various measures: the Self-Strengthening Movement (1861–1895), which aimed to develop China's industry and modernize its armies and navies; the Reform Movement of 1898, which sought to overhaul China's imperial system; and the Revolution of 1911, which overthrew the monarchy. Despite these efforts, none succeeded in saving China. The plundering by Western powers, combined with the chaotic power struggles among domestic warlords after the monarchy's collapse, drained China's resources. Once the richest country in the world, China was reduced to one of the poorest.

Having exhausted all means of reform, some Chinese eventually concluded that the root of China's struggles lay in its culture. In 1919, the radical May Fourth New Culture Movement broke out. In a desperate attempt to find solutions to save the country, some Chinese intellectuals blamed Confucianism, particularly Neo-Confucianism, for China's failures, accusing it of restricting individual freedom and social progress. They advocated dismantling Confucianism and replacing it with Western-style liberal democracy and capitalism. Other Chinese intellectuals, however, were skeptical of that path and instead turned to another Western ideology—Marxism—believing that socialism aligned more closely with the Confucian ideal of an egalitarian and harmonious society. This ideological divide led to a confrontation between the KMT and the CCP. Ultimately, the side with the support of the majority of the Chinese people prevailed, and the KMT retreated to the Chinese island of Taiwan across the Taiwan Strait. In the first three decades following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese, while facing a blockade by Western powers, did many groundwork for its latter development, including land reform, women's liberation, universal free education and healthcare, and basic industrial infrastruture building. Many lessons were learned from trial and error. In 1978, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the CCP re-examined the lessons from the previous thirty years and decided to implement reform and opening-up policies. This initiative aimed to unleash people's potential by introducing market mechanisms into the Chinese economy while preserving the structural advantages of its socialist system.

We have all witnessed what followed. In just 40 years, China has been miraculously transformed from a poor and weak country into the world's second-largest economy, achieving a 42-fold increase in GDP. It has become the world’s largest manufacturing powerhouse, lifted 770 million people out of poverty, created a middle class of over 400 million, and increased per capita income by 23 times. Additionally, the average life expectancy in China now surpasses that of the United States. China has also emerged as the world's largest investment market, largest consumer market, and largest trading partner with more than 130 countries, playing an increasingly significant role in the global economy and international affairs. Unlike some Western powers that engage in hegemonism, bullying, intervention, containment, subversion, and coercive diplomacy, China’s foreign policies adhere firmly to the five guiding principles of international relations: mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. These principles are further supported by China's Belt and Road Initiative for global common prosperity and its initiative to establish a community with a shared future for mankind. These foreign policies reflect obvious Confucian influences and are gaining support from an increasing number of countries worldwide.

Once again, China has entered one of its most prosperous periods, and it did so not through aggression, colonization, conquest, or plundering other nations, but by leading its own people to work hard and fostering cooperation with other countries for mutually beneficial outcomes. This remarkable achievement has restored the Chinese people's confidence in their own philosophy, culture, system, and chosen path. The core values of Chinese civilization, established by Confucianism, have been integral to this success. Without these values, socialism with Chinese characteristics and Chinese-style modernization—a unique form of modernization that emphasizes civilized values, equality, justice, common prosperity, green economy, peaceful development, and international cooperation—would not have been possible. Confucianism embodies the accumulated wisdom of the Chinese people, highlighting the unity, balance, and harmony between man and nature, individuals and society, law and virtue, morality and economy, rulers and the people, as well as among individuals themselves. With its holistic vision, idealism, magnanimity, and positive outlook, Confucianism has served as both a unifying force and a source of strength for the Chinese people, inspiring them to continually improve themselves and their country, and giving China its competitive edge. Although Confucianism must adapt to evolving times, as it has done throughout history, it remains deeply ingrained in the language, culture, mindset, behavior, and consciousness of the Chinese people. For more than two millennia, Confucianism has been repeatedly tested, enriched, and replenished by successive generations of Chinese. It will undoubtedly continue to influence their pursuit of a brighter future. (See Darwinism and Confucianism.)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment