Tango is not just a fascinating dance—it is a rich philosophy, culture, and way of life. The search of tango is the search of connection, love, fellowship, unity, harmony, and beauty—an idealism that is not consistent with the dehumanizing reality of the modern world. The world divides us into individuals, but tango brings us together as a team. In tango we are not individualists, feminists, nationalists, Democrats, or Republicans—we are simply human, intertwined and interdependent. Tango invites us to tear down walls, build bridges, and rediscover our shared humanity through connection, cooperation, accommodation, and compromise. It is a dance that reminds the world how to love.

Showing posts with label Confucianism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Confucianism. Show all posts

January 26, 2024

Understanding China: Yellow River and the Character of the Chinese Nation

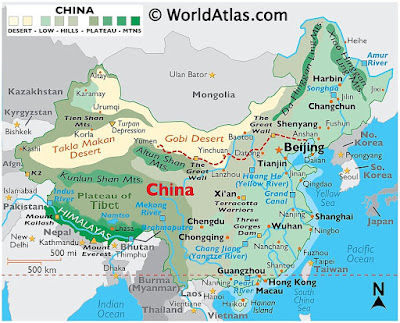

China is a vast country, comparable in size to Europe. Roughly two-thirds of its landmass is mountainous, with terrain that rises in the west and gradually descends toward the east. The western region is dominated by towering mountain ranges, many exceeding 5,000 meters in elevation. Chief among them are the Himalayas, whose highest peak soars to 8,848 meters above sea level. In contrast, the eastern region transitions into a broad plain, dipping to below 50 meters above sea level.

The Yellow River, China’s second longest, originates in the Bayan Har Mountains of Qinghai Province at an altitude of 5,369 meters. It flows from west to east, traversing the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the Loess Plateau, the Inner Mongolia Plateau, and the North China Plain, before emptying into the Bohai Sea. Its basin covers approximately 795,000 square kilometers and spans nine provinces: Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, and Shandong.

Millions of years ago, the area east of the Taihang Mountains in central North China (indicated on the map below) was part of the ocean. The North China Plain—occupying the upper two-thirds of the green area on the map—was formed through the accumulation of sediment from the Yellow River over millions of years. Flowing through the Loess Plateau, the river collects an immense amount of silt, making its water literally yellow. It transports 1.6 billion tons of sediment downstream every year, about a quarter of which settles along the river’s course, and the rest washes into the Bohai Sea. The buildup of silt in the river’s lower reaches gradually raises the riverbed. Every once in a while, the Yellow River changes its course due to the blockage of large amounts of sediment. Wherever the terrain is lower, that's where the diverted river flows, carrying sediment with it and filling in depressions. For millions of years, sediment from the Yellow River has filled the low areas back and forth, created the vast North China Plain, which is larger than Britain. Today, the Yellow River is still reclaiming land from the sea and steadily pushing the coastline eastward. Scientists estimated that the Bohai Sea may be filled in within a few hundred years, further expanding the North China Plain.

Archaeology has revealed that eight thousand years ago people were already living on this land created by the Yellow River. The North China Plain—the cradle of Chinese civilization—has long been the most densely populated, economically vibrant, and culturally prosperous region in China, thanks to its fertile soil, temperate climate, and abundant rainfall brought by the Pacific monsoon, which made this region ideal for agriculture. While the Yellow River has nourished the people living on this land, it has also brought them devastation. As the riverbed rose, people were forced to continuously reinforce embankments to protect farmland and settlements on both sides. Over time, the riverbed gradually rose above the surrounding ground; in some areas, it now stands 5–10 meters above the terrain, turning the river into a "hanging river." Once an embankment breaks, it unleashes catastrophic flooding, sweeping away everything in its path. Historical records show that, in the past 2,500 years, the Yellow River has burst its banks 1,593 times and changed its course 26 times. Each time the river floods, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of people are killed or displaced. The Yellow River flood of 1897, related to Western invasion, domestic unrest and poor maintainance, claimed the lives of two million (some say seven million) people. Efforts to manage the river have never stopped since ancient times. Perhaps no people in the world have had such a complex and paradoxical relationship with their mother river as the Chinese. They are deeply grateful for the nourishment she provides, yet they also harbor sorrow and frustration over her destructive force. But it is precisely through this intimate, turbulent relationship that the Yellow River has forged the perseverance, tenacity, hard work, and resilience of the Chinese people.

Chinese parents often use strict discipline to train their children, preparing them to face the severe challenges of life. This is not unrelated to the fact that they themselves grew up under the temper of the Yellow River. Westerners who embrace individualism tend to prioritize children’s independence and self-expression. Chinese parenting emphasizes perseverance, endurance, responsibility, and team spirit. This approach is deeply connected to their harsh living environment. In front of the Yellow River, individuals are insignificant. Controlling the Yellow River relies on collective strength. Therefore, Chinese philosophy places great emphasis on collectivism and teamwork. Western philosophy conceptualizes individuals as independent actors, prioritizing personal interests over collective concerns. In contrast, Chinese philosophy perceives individuals as interconnected and interdependent members of society with a common destiny and shared interests and responsibilities. This prioritization of collective concerns over individual interests is heavily influenced by their shared burden imposed by the Yellow River.

The fertile, rich, yet troubled land of the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River allows the people living there to not only enjoy the blessings of the river but also face the challenges it brings. This paradox has nurtured the dialectical thinking of the Chinese people. Unlike Westerners who often perceive things in stark black-and-white terms, the Chinese recognize that opposing forces (yin and yang) coexist in all things, much like the river itself. Good fortune and misfortune, they believe, are intertwined. This awareness enables them to approach life with balance and equanimity, remain cautious in times of peace, and find opportunity in adversity. Chinese philosophy discourages simplistic and extreme ideologies, such as individualism, feminism, Darwinism, unipolarism, hegemonism, or zero-sum thinking. Instead, it embraces the idea that diverse elements complement and coexist peacefully, akin to the harmony between the sexes. The Confucian doctrine of the mean advocates for moderation, balance, and harmony amid contradiction. This seemingly modest approach allows them to coexist harmoniously within an environment that is both contradictory and integrated. This orientation also underlies the traditional Chinese aversion to factionalism and partisan politics—a perspective shaped, in part, by their experience with the Yellow River’s unpredictability and the need for unity in the face of natural disaster. (See Philosophies that Separate Two Worlds.)

Managing the Yellow River—an enormous task that spans vast territories and demands massive manpower, meticulous planning, and nationwide coordination—necessitates a unified, centralized government with strong planning and organizational capabilities. This need has deeply influenced China's political development. The emphasis on stability in Chinese political culture is rooted in the recognition that only a stable and capable government can manage a river of such scale. In fact, the origins of Chinese state power can be traced back to river management. Dayu, the founder of the Xia Dynasty (circa 2070 BC–1600 BC), the first dynasty recorded in Chinese history, was revered for organizing the people to regulate the Yellow River. With thousands of years of experience, the Chinese have become skilled at mass mobilization and organization, honing themselves into the most disciplined and well-managed people. This collective capability has enabled China to weather its greatest challenges. By contrast, the Western political model—based on individualism and partisanship, where competing interest groups take turns governing—may serve special interests well, but it does not align with China’s unique needs.

In conclusion, the character, philosophy, culture, and political system of the Chinese nation are deeply rooted in their relationship with the Yellow River. This influential river nurtures the people to embody qualities such as resilience, solidarity, generosity, magnanimity, and wisdom—reflecting the attributes of their mother river. A civilization that has endured and overcome such severe challenges for millennia is formidable—and must never be underestimated.

(See also: Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and the Chinese-Style Modernization.)

March 1, 2023

Darwinism and Confucianism

English naturalist and biologist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in Western intellectual history. His groundbreaking work, On the Origin of Species (1859), fundamentally reshaped the way the West understands the natural world.

Darwin's theory is based on the idea of natural selection. Organisms with advantageous traits are more likely to survive and reproduce. This is largely due to the fact that variations occur within all populations of organisms. Throughout the lives of the individuals their genomes interact with their environments to cause random mutations arise in the genome, which can be passed on to offspring. If a particular trait enhances survival and reproductive success, it becomes more prevalent over generations, driving the evolution of species.

Although most scientists now accept evolution as descent with modification, not all concur with Darwin's assertion that natural selection is the primary—though not exclusive—mechanism behind it. Some advanced competing theories that assigned a more limited role to natural selection. Critics argued that Darwin overemphasized the "struggle for existence" and "survival of the fittest" among individuals, while underestimating the role of interdependence, cooperation, and ecological balance—both within and among species—in ensuring survival and evolutionary success. (See Pluralism vs. Monism.)

Darwin’s theory revolutionized biology and our understanding of life itself, but it also produced adverse impacts. Concepts such as "struggle for existence" and "survival of the fittest" were misapplied to human societies, giving rise to ideologies like social Darwinism, individualism, exceptionalism, racism, "law of the jungle" thinking, zero-sum competition, and unipolar hegemony. These distortions eroded human solidarity, social harmony, and prospects for peace. The harm caused by these ideologies should not be underestimated: Western civilization, particularly in the post-Darwin era, has been marked by imperialism, colonialism, conquest, genocide, exploitation, and plundering—with Darwin’s fellow countrymen playing a central role. These ideologies also fueled Western capitalism that led to brutal competitions, massive inequality, resource depletion, ecological destruction, and environmental degradation. (See Democracy vs. Plutocracy.)

By contrast, Darwinism has had less ideological influence in the East, where Confucianism has long shaped cultural and philosophical foundations. Confucian thought emphasizes harmony between humanity and nature, the shared destiny of humankind, and the ideal of peaceful coexistence. It offers a holistic worldview that sees the universe as an interconnected whole rather than a battlefield of competing interests. While acknowledging contradictions and tensions, Confucianism seeks to resolve them through balance, mutual dependence, and the integration of diverse elements—discouraging antagonism and the elimination of adversaries. (See Philosophies that Separate Two Worlds.)

Where Darwinism stresses the instinct for individual survival, Confucianism elevates the moral and intellectual potential of human beings above primal impulses. Confucius articulated this ethical vision through five core virtues: 仁 (ren—benevolence, compassion, and love), 義 (yi—righteousness, justice, and equity), 禮 (li—propriety, morality, and law), 智 (zhi—wisdom, knowledge, and reason), and 信 (xin—trust, integrity, and good faith). Unlike the animal world, where the strong prey upon the weak, Confucianism holds that human civilization must transcend the "law of the jungle." The flourishing of society depends on moral cultivation, social cooperation, and the collective pursuit of the common good. (See Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and Chinese-Style Modernization).

While it is still too early to render a definitive judgment on the relative merits of Eastern versus Western philosophies, current global trends suggest that values rooted in enlightened civilization, collectivism, cooperation, and shared prosperity may ultimately serve humanity better than those driven by barbarism, individualism, selfishness, and ruthless competition. The rise of the East and the relative decline of the West point to the enduring relevance of Confucian values. This philosophical divergence also echoes in cultural expressions such as tango (see A Dance that Challenges Modern Ideologies).

December 9, 2021

Democracy vs. Plutocracy

American political thought is fundamentally atomistic, rooted in the belief that individuals are autonomous beings endowed with inalienable rights to pursue their own self-interest. This philosophical foundation normalizes intense competition, where a few emerge as winners while the majority are left behind. Those who succeed in this system often consolidate their power by forming political parties, which claim to represent the public but primarily compete for influence and control.

Elections serve as the formal mechanism through which these parties alternate power. Over time, practices such as political donations, lobbying, and media campaigning have been redefined as forms of free speech, allowing those with greater resources to dominate the political arena. As a result, elections become increasingly ideological and media-driven, shaped by those who have the means to sway public opinion. Ultimately, this dynamic fosters a political landscape in which policies tend to favor the wealthy, deepening social and economic inequality.

With elections increasingly vulnerable to financial influence, misinformation, and character attacks, American politics has become deeply contentious. Elected officials often prioritize performative rhetoric and media attention over effective governance, focusing more on pleasing donors and securing re-election than advancing the public good. The frequent shifts in party control lead to erratic policy reversals, undermining long-term planning and institutional stability. Each administration tends to overspend, accumulate debt, and resort to printing money to inflate short-term approval—leaving the economic consequences to future governments. Meanwhile, partisan gridlock paralyzes decision-making and intensifies social division.

Despite these dysfunctions, many Americans still regard the current system as the only legitimate form of democracy. In practice, however, the U.S. political system operates more as a partisan democracy than a people’s democracy. Increasingly, scholars argue that it has morphed into a plutocracy—rule by the wealthy and well-connected. Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz famously characterized the United States as a nation “of the 1%, by the 1%, and for the 1%.” Backed by powerful special interests, political elites often sideline the needs and voices of the broader population.

The consequences of this distorted system are stark. The U.S. has the highest levels of inequality among developed nations, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, it suffered a death toll over 170 times higher than China’s and an infection rate 1,600 times greater. Decades of financial mismanagement have pushed the national debt beyond $30 trillion, much of it channeled into private contractors, defense budgets, and corporate subsidies. Meanwhile, deep-rooted social problems—ranging from racial conflict and poverty to drug addiction and gun violence—continue to plague the nation.

With less than a quarter of the population of China or India, the U.S. nonetheless has the world’s largest prison population. Its healthcare system is the most expensive globally, yet millions remain uninsured or underinsured. Retirement ages have steadily climbed, placing increasing burdens on the elderly. According to the U.S. Life Insurance Guide, the average retirement age is 67.9 for men and 66.5 for women, compared to China’s 60 for men, 55 for women. Public education is in decline, infrastructure is aging, and the country has been at war for 229 of its 245-year history. These conflicts, often justified in the name of “American values,” perpetuate high military spending, weapons exports, and global dominance—primarily serving entrenched economic and political interests.

Although this system is labeled a democracy, the average American has increasingly little influence over the decisions that shape their daily lives.

In contrast, Chinese political thought is fundamentally holistic, emphasizing the interdependence of individuals within the broader social fabric. Human rights in China are framed in terms of collective well-being rather than individual autonomy. These rights encompass not only personal freedom but also values such as coexistence, equality, cooperation, and social harmony. Whereas American thought tends to view individuals as independent actors pursuing self-interest, Chinese thought sees people as intrinsically connected, with mutual obligations to family, community, and society. Rooted in Confucian tradition, this perspective prioritizes ethical behavior, consensus-building, and the pursuit of communal interests as essential to maintaining social stability and order. (See Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and Chinese-Style Modernization.)

China adopts a model of people’s democracy, prioritizing collective governance over partisan competition. While individual interests vary, leadership is expected to represent the broader will of the population. With a 5,000-year tradition of governance, China has historically recognized both the risks of factionalism and the importance of unified political leadership. The Communist Party of China (CPC), comprising nearly 100 million members, positions national interest above partisan agendas. Leadership selection occurs every five years through the CPC National Congress and the National People’s Congress, with candidates evaluated based on character, competence, and proven achievement, rather than rhetoric or ideology. Policy development involves extensive research, public consultation, and meticulous planning to balance short-term priorities with long-term national goals. Unlike the U.S., where governance often reflects special interest influence, China’s system seeks to foster a just and harmonious society rooted in shared prosperity. Institutional safeguards—including collective leadership, term limits, anti-corruption measures, public supervision, and internal discipline—aim to enhance accountability and prevent authoritarianism.

Differences in human rights perspectives shape how each country approaches key issues. In the U.S., COVID-19 precautions were largely seen as a matter of personal choice, with individual liberty prioritized over collective protection. In contrast, China placed public health first, with temporary restrictions widely accepted for the greater good. Similarly, Americans often view gun control as an infringement on personal freedom, whereas the Chinese regard strict firearm laws as essential for public safety. In the U.S., business regulation is frequently seen as a constraint on economic freedom, while in China, such oversight is viewed as necessary to reduce inequality. Intellectual property in the U.S. is tightly protected, often limit accessibility and innovation, while China promotes shared technological advancement to accelerate national development. And while the U.S. frequently invokes individual rights to justify foreign interventions, China considers such actions—including the instigation of color revolutions and conflicts under the banner of democracy—as violations of national sovereignty and human rights.

No political system is immune to failure. History teaches that if a nation fails to confront its ideological, institutional, and systemic flaws, decline is inevitable. The dominance of special interests—such as corporate lobbies and the military-industrial complex—erodes democratic legitimacy and public trust. Drawing from China’s long history, the collapse of a democracy under the weight of corruption and plutocracy may take less than three centuries (see The Vicious Circle of Regime Change). This is why Chinese political culture values collectivism and egalitarianism over individualism. As China rises, Confucian values are poised to play a larger role in shaping global political thought—an evolution worth noting and, perhaps, celebrating. (See Pluralism vs. Monism.)

November 18, 2021

Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and Chinese-Style Modernization

Five thousand years ago, tribal alliances and city-states emerged in the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of East Asia. Over time, these civilizations coalesced into a single entity—China—which expanded steadily until it met formidable natural barriers on all sides. To the northeast lay the icy expanse of Siberia; to the north, the vast, desolate Mongolian deserts. The west was dominated by towering mountain ranges, with peaks exceeding 5,000 meters, including the Himalayas, home to Mount Everest at 8,848 meters. The southwest featured the rugged Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and dense tropical jungles, while the southeast and east faced the immense Pacific Ocean. In ancient times, these geographic obstacles were virtually impassable, effectively isolating China from the outside world. Shielded by these natural defenses, the Yellow and Yangtze River basins enjoyed a temperate climate and abundant rainfall brought by the Pacific monsoon, making them ideal for agriculture. This unique geographical setting played a decisive role in shaping the character and development of Chinese civilization.

The Chinese civilization was able to develop its unique and remarkable culture largely due to geographical barriers that limited outside influence and prevented foreign aggression. This allowed China to remain the only ancient civilization to develop without interruption for over five millennia. They also limited the Chinese worldview. Enclosed by these barriers, the Chinese believed their land constituted the main body of the world, which they called tianxia—literally, “all under heaven.” The Yellow River and Yangtze River basins lay at its center, thus, China was named Zhongguo, meaning “central country.” Blessed with fertile lands and abundant resources, China was far more advanced than the surrounding frontier regions. Chinese peasants, living in kinship-based villages, grew deeply attached to their land and were uninterested in the barren territories beyond, fostering a reserved and inward-looking temperament. Rather than expanding militarily, the Chinese built the Great Wall to protect themselves from northern nomads. This 21,000-kilometer Wall, located along the 400 mm isoprecipitation line and spanning from east to west, symbolized the divide between sedentary agricultural societies and nomadic cultures. Nomadic tribes who crossed the Wall and settled in China were eventually assimilated into Chinese farming culture, becoming Chinese themselves. Thus, Chinese civilization, shaped by its geography, epitomized the triumph of a settled, productive way of life over a nomadic, predatory one. The Chinese have long taken pride in their land, culture, and lifestyle, as China has been the world’s most advanced civilization until the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

This geographical seclusion also fostered a monistic rather than pluralistic vision of the world. Unlike the Western notion of a world composed of many sovereign states, the ancient Chinese saw the world as an integrated whole, with China as its sole civilized center. Surrounding ethnic tribes were viewed as vassals within the Chinese tributary system, many of which were sinicized over time and became part of China.

In 221 BC, the state of Qin (pronounced "chin" from which "China" is derived) defeated all rival states and unified the country. Qin standardized laws, scripts, currency, weights, measures, and vehicle tracks, abolishing feudal fiefdoms in favor of a system of prefectures and counties. Scholars have noted that China’s geography, which necessitated large-scale irrigation and water management, contributed to the emergence of a collectivist, centralized state focused on unity and cooperation (see Understanding China: Yellow River and the Character of the Chinese Nation). Qin's system, inherited by all subsequent dynasties, laid the groundwork for China's enduring unification, stability, and prosperity. In turn, this culture has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for assimilation and integration, inspiring neighboring states to emulate it. The Confucian ideal of dayitong (great unity) echoed this holistic vision. Throughout history, many ethnic groups that partially or entirely conquered China were eventually assimilated into Chinese culture. This process of sinicization, rather than military expansion, is responsible for China's vast territory.

Aligned with this holistic worldview, Confucianism promotes a vision of society as an integrated whole. The Datong (大同) society, an ideal described in Confucian classics, imagines a harmonious world where the wise govern, the honest live peacefully, the vulnerable are protected, and crime is nonexistent. Contrast sharply with Western individualism, which emphasizes personal interests and often pits the strong against the weak, causing people to be egocentric and belligerent, Confucianism envisions society as an extended family, where members cooperate, seek common ground, prioritize communal interests over personal ones, and work together as a team. In Confucianism, individuals are not viewed as isolated and autonomous but as integral members of society, born into specific relationships with defined roles and responsibilities. They adhere to etiquettes designed to maintain social harmony—akin to tango dancers observing milonga codes in the milongas. These etiquettes or proprieties were practiced even before Confucius’s time, by the people of the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th–8th century BC). Confucius (551 BC–479 BC) and his disciples were scholars and ardent advocates of these ancient rites. In essence, Confucianism is rooted in a tradition that remains central to Chinese culture.

This tradition emphasizes the importance of harmonious relationships among people and society as a whole. Confucianism holds that societal stability depends on a solid foundation: the people. A ruler, like the head of a family, derives authority from the people and is responsible for their welfare. As Confucius said, “The ruler is the boat; the people are the water. Water can carry the boat, or overturn it.” Mencius (372 BC–289 BC), another prominent Confucian sage, similarly underscored the central role of the people, asserting that they are the most important, followed by the state, with the monarch being the least. Confucianism teaches that a ruler’s legitimacy stems from the support or mandate of the people, and an unrighteous ruler will lose that mandate. In essence, Confucianism represents a people-centered collectivist humanism, in contrast to the individualistic humanism of the West. This collectivist humanism has shaped Chinese governance ideals that continue to this day—from Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People, to the founding of the People's Republic of China, to the Communist Party’s motto of serving the people, to Xi Jinping’s call for a community with a shared future for mankind. (See Democracy vs. Plutocracy.)

Rooted in this people-centered collectivist humanism, Confucianism advocates for benevolent governance. Confucius believed that benevolence is the essence of human nature, distinguishing humans from animals. Unlike Machiavelli, who separated morality from politics, Confucius saw morality as central to governance. A ruler must be a saint at heart, a moral leader, and a role model. Only through self-cultivation can he manage his family, govern his country, and bring peace to the world. Confucius emphasized the importance of proprieties (etiquettes), but he stressed that rule observances must be grounded in benevolence, or they become hollow gestures. His followers, however, divided into two camps. The school that emphasized benevolence was later recognized as the orthodoxy of Confucianism. The school that prioritized proprieties evolved into Legalism. The unification of China by the Qin state in 221 BC was achieved through the use of military power and severe penal laws under the influence of the Legalist school of thought. Due to its brutality, the Qin Dynasty survived with only two rulers before it was overthrown by widespread rebellions. Learned from this lesson, in 134 BC, Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty accepted the advice of a Confucian scholar, Dong Zhongshu (179 BC–104 BC), to replace other schools of thought with Confucianism and to implement benevolent rule. Since then, Confucianism has become the official ideology of China. Unlike Christianity and Machiavellianism, which assert that human nature is inherently evil, Confucianism holds that human nature is inherently good, therefore opposes the Legalist reliance on strict laws and harsh punishments as primary tools of governance, instead advocates for rule through virtue and education. This approach gave rise to the Chinese tradition of prioritizing morality and learning.

In 587 AD, Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty established the imperial examination system, linking education with civil service. This meritocratic system played a pivotal role in shaping China's effective political bureaucracy. It further promoted Confucian learning, opened the way for talented individuals from all walks of life to enter politics, and gave rise to the scholar-official class. China's modern civil servant selection system is a continuation of this legacy. Many researchers argue that, compared to Western electoral democracy, China’s meritocratic system is better equipped to produce leaders with moral integrity, practical knowledge, and strong abilities, as evidenced by China's illustrious history and recent economic achievements. However, in the past, the imperial examination system failed to prevent the recurrence of dynastic cycles. Today, China seeks to address this through political reforms, such as collective decision-making, age and term limits for officials, clean government initiatives, self-correction mechanisms, disciplinary inspection, anti-corruption campaigns, public supervision of the government, reporting and petitioning systems, and impeachment procedures. These efforts aim to improve governance, ensure accountability, and prevent the emergence of autocracy.

Based on this people-centered collectivist humanism, Confucianism calls for the equitable distribution of wealth and condemns prioritizing economic interests over morality, using unethical means to accumulate wealth, competing for monetary gain, and widening the gap between rich and poor. Confucians argued that the ruler should disperse the nation's wealth among the people rather than competing with the people for profit. As Confucius said, “Rulers should not worry about not having enough, but about inequality.” This ethos inspired Chinese rulers throughout ages to adopt egalitarian policies and implement benevolent governance. However, the emphasis on morality over economy historically led to the devaluation of merchants in traditional Chinese society, where they ranked below scholars, farmers, and craftsmen. China's early post-1949 policies reflected this Confucian tendency, prioritizing morality and scholarship over economic development. During the reform and opening-up era initiated by Deng Xiaoping, however, the government shifted policy to encourage business and entrepreneurship under the slogan “letting some people get rich first.” Subsequently, the Chinese government targeted poverty alleviation programs and anti-monopoly efforts, upholding Confucian egalitarianism while recognizing the importance of economic development as a means to achieve common prosperity. The Confucian emphasis on production over commerce has also contributed to China’s physiocratic tradition, favoring agriculture and manufacturing over speculative capitalism, which often leads to economic hollowing, corruption, inequality, and systemic collapse (see Mammonism).

Another Confucian concept that has a far-reaching influence is the Doctrine of the Mean, which champions moderation and harmony. Confucius saw harmony as the fundamental law of nature and excess as the cause of reversal and disorder. He regarded humility, politeness, impartiality, and avoiding extremes as the qualities of a true gentleman. Deviation from this principle could lead to disastrous consequences (see Meeting in the Middle). This Confucian proposition is incompatible with Western liberalism and individualism. Chinese people lack the arrogant, bigoted, extreme, domineering and aggressive spirit of many Westerners, Confucianism is the main reason. This emphasis on moderation, balance and harmony has discouraged the Chinese from engaging in Western-style partisan politics, which tend to create division, conflict, hostility and polarity. While Western culture prioritizes partisanship and competition, Chinese culture values unity and cooperation. The Chinese tend to approach issues in a holistic, comprehensive, and balanced manner. Today's Chinese leadership is acutely aware that both morality and personal freedom are important and an excessive focus on either one can be harmful. Overemphasis on morality can suppress initiative and creativity, while overemphasis on individual liberty can exacerbate conflict and inequality. Striking a balance, however, is no easy task. Historically, Confucian morality was transformed by Neo-Confucianists into a rigid ideology that restricted personal freedom. Western liberalism and individualism represent the opposite extreme. The Chinese now strive to find a balance that aims at a society respecting both individual freedom and social morality (see Pluralism vs. Monism).

The peaceful life of the Chinese has finally come to an end. In 1840, Western powers used opium, warships and cannons to finally bombard China's door open, forcing the Qing Dynesty (1644-1911), the last Chinese dynesty, to sign a series of unequal treaties for ceding territories and indemnities. Confronted with this humiliating defeat and the stark disparity between an agricultural China and the already industrialized West, the Chinese began seeking ways to save their country. Over the eight decades following the Opium War, they attempted various measures: the Westernization Movement (1861–1895), which aimed to develop China's industry and modernize its armies and navies; the Reform Movement of 1898, which sought to overhaul China's imperial system; and the Revolution of 1911, which overthrew the monarchy. Despite these efforts, none succeeded in saving China. The plundering by Western powers, combined with the chaotic power struggles among domestic warlords after the monarchy's collapse, drained China's resources. Once the richest country in the world, China was reduced to one of the poorest.

After exhausting all means of reform, some Chinese eventually concluded that the root of China's struggles lay in its culture. In 1919, the radical May Fourth New Culture Movement broke out. In a desperate attempt to find solutions, some Chinese intellectuals blamed Confucianism, particularly Neo-Confucianism, for China's failures, accusing it of restricting individual freedom and social progress. They advocated dismantling Confucianism and replacing it with Western-style liberal democracy and capitalism. Other Chinese intellectuals, however, were skeptical of Western liberalism and capitalism and instead turned to another Western ideology—Marxism—believing that socialism aligned more closely with the Confucian ideal of a harmonious society. This ideological divide led to a confrontation between the KMT and the CCP. Ultimately, the side with the support of the majority of the Chinese people prevailed, and the KMT retreated to the Chinese island of Taiwan across the Taiwan Strait. In the first three decades following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese, while facing a blockade by Western powers, did many groundwork for its latter development, including land reform, women's liberation, universal free education and healthcare, and basic industrial infrastruture building. Many lessons were learned from trial and error. In 1978, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the CCP re-examined the lessons from the previous thirty years and decided to implement reform and opening-up policies. This initiative aimed to unleash people's potential by introducing market mechanisms into the Chinese economy while preserving the structural advantages of its socialist system.

We have all witnessed what followed. In just 40 years, China has been miraculously transformed from a poor and weak country into the world's second-largest economy, achieving a 42-fold increase in GDP. It has become the world’s largest manufacturing powerhouse, lifted 770 million people out of poverty, created a middle class of over 400 million, and increased per capita income by 23 times. Additionally, the average life expectancy in China now surpasses that of the United States. China has also emerged as the world's largest investment market, largest consumer market, and largest trading partner with more than 130 countries, playing an increasingly significant role in the global economy and international affairs. Unlike some Western powers that engage in hegemonism, bullying, intervention, containment, subversion, and coercive diplomacy, China’s foreign policies adhere firmly to the five guiding principles of international relations: mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. These principles are further supported by China's Belt and Road Initiative for global common prosperity and its initiative to establish a community with a shared future for mankind. These foreign policies reflect obvious Confucian influences and are gaining support from an increasing number of countries worldwide.

Once again, China has entered one of its most prosperous periods, and it did so not through aggression, conquest, or plundering other nations, but by leading its own people to work hard and fostering cooperation with other countries for mutually beneficial outcomes. This remarkable achievement has restored the Chinese people's confidence in their philosophy, culture, system, and chosen path. The core values of Chinese civilization, established by Confucianism, have been integral to this success. Without these values, socialism with Chinese characteristics and Chinese-style modernization—a unique form of modernization that emphasizes civilized values, equality, justice, green economy, common prosperity, peaceful development, and international cooperation—would not have been possible. Confucianism embodies the accumulated wisdom of the Chinese people, highlighting the unity, balance, and harmony between man and nature, individuals and society, law and virtue, morality and economy, rulers and the people, as well as among individuals themselves. With its holistic vision, magnanimity, idealism, and positive outlook, Confucianism has served as both a unifying force and a source of strength for the Chinese people, inspiring them to continually improve themselves and their country, and giving China its competitive edge. Although Confucianism must adapt to evolving times, as it has done throughout history, it remains deeply ingrained in the language, culture, mindset, behavior, and consciousness of the Chinese people. For more than two millennia, Confucianism has been repeatedly tested, enriched, and replenished by successive generations of Chinese. It will undoubtedly continue to influence their pursuit of a brighter future. (See Darwinism and Confucianism.)

October 10, 2020

Lessons from Tango

Zoom out to see the larger picture, or zoom in to see only yourself — the outcomes are different.

Become one with your partner, or remain alone in your own world — the outcomes are different.

Think from your partner’s perspective, or think only of yourself — the outcomes are different.

Strive for shared well-being, or chase personal success — the outcomes are different.

Find common ground, or focus on differences — the outcomes are different.

Foster cooperation, or fuel conflict — the outcomes are different.

Show flexibility, or cling to rigidity — the outcomes are different.

Compromise and adapt, or insist and resist — the outcomes are different.

Meet halfway, or assert yourself — the outcomes are different.

Seek balance, or pursue extremes — the outcomes are different.

Maintain harmony, or pursue dominance — the outcomes are different.

Choose humility, or embrace hubris — the outcomes are different.

Act with empathy, or act with aloofness — the outcomes are different.

Forgive, or hold grudges — the outcomes are different.

Build a bridge, or build a wall — the outcomes are different.

The first path reflects the nobility of human nature; the second reveals its smallness.

The former — aligned with the spirit of tango — brings peace, cohesion, and beauty.

The latter — rooted in ego and isolation — breeds tension, division, and dissonance.

October 24, 2018

Pluralism vs. Monism

Pluralism asserts that the universe comprises distinct entities that exist independently, each maintaining its own unique essence. In contrast, monism contends that all seemingly separate elements are interconnected components of a unified whole, bound by an underlying, consistent foundation. While pluralism highlights the diversity of the world, monism emphasizes its unity. These perspectives reflect broader intellectual traditions—pluralism aligns with the atomistic and analytical thinking of the West, while monism embodies the holistic and integrative philosophy of the East.

Pluralism upholds the principles of individual distinction, autonomy, and self-determination, advocating for personal liberty, individual rights, private ownership, competition, and free-market economics. In contrast, monism views individuals as interconnected members of a unified society, emphasizing collective interests, cooperation, equality, fraternity, social responsibility, and communal well-being. These philosophical paradigms have profoundly influenced economic and political structures, shaping governance and societal values. Yet the fundamental question remains: which approach best serves humanity’s long-term interests and leads us toward a more sustainable and prosperous future?

Aristotle once stated, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Historically, monism dominated philosophical thought, as early human societies recognized unity and cooperation as essential to survival and prosperity. Over time, the rise of modern science and technology empowered individuals, fostering self-reliance and encouraging a shift toward individualism and pluralism. These ideologies champion personal liberty and diversity, shaping multiculturalism that embraces nonconformity, LGBTQ+ rights, same-sex marriage, and other iconoclastic values. They also contribute to broader philosophical shifts, including relativism, which questions absolute distinctions between truth and falsehood, morality, and aesthetics; skepticism toward intellectualism, reason, and science; and policies such as affirmative action, aimed at supporting marginalized groups and alternative lifestyles. While these cultural transformations have promoted inclusion and innovation, they have also contributed to heightened polarization, societal fragmentation, ideological discord, and partisan strife (see Tango and Individualism).

Individualism and pluralism, rooted in the "law of the jungle" mindset, lack respect for equality, morality, and the common good. This has created social instability not only within societies that champion these ideologies but also across the globe, as evidenced by the growing moral decay, societal fragmentation, political dysfunction, and widespread lawlessness in the United States, the lack of moral integrity among its political elites, and the destructive impact of their self-serving, hegemonic, and coercive foreign policies on the world (see Darwinism and Confucianism).

These ideologies overlook a fundamental truth: human beings are inherently interconnected and interdependent. The survival and progress of our species rely on cooperation and unity. A thriving society must be built on philosophies that foster cohesion, shared moral principles, social stability, and good governance. When individuals are set against one another in pursuit of personal gain, the result is division, animosity, and chaos. This has been evident in the turmoil following U.S.-led efforts to "liberate" populations, leading to humanitarian crises and refugee displacement—challenges further exacerbated by open-border policies and multiculturalism at home. If we continue to advance radical liberalism—prioritizing absolute personal freedom over collective welfare, rejecting any form of authority as oppressive, labeling democracy as “tyranny of the majority,” inflaming gender conflicts, politicizing education, media, and law, and fragmenting society into increasingly isolated identity groups—the social fabric will continue to erode.

While liberalism has historically played a crucial role in unlocking human potential and driving capitalism’s ascent in the West, its excessive emphasis on individualism has, in many ways, become counterproductive. As one reader insightfully observed, “Freedom and human rights movements have placed a heightened focus on individuality. As a result, an inflated self-image diminishes our ability to see the world as a unified whole. This inflated sense of self may also underlie many modern psychological struggles—loneliness, depression, and mental distress. If we can zoom out and recognize ourselves as a small part of a vast universe, a truth unchanged since the Big Bang, we may rediscover the beauty in ancient natural laws and adopt a healthier perspective on ourselves and the world (see A Wise Voice).” The outcome, unfortunately, has been a re-concentration of wealth, resources, and political power in the hands of a few, only this time it is done not under monarchies or aristocracies, but the guise of free competition.

Observing capitalism’s success in the West, the East—while remaining rooted in its holistic philosophy and Confucian values—has increasingly fostered human initiative and creativity, which has also brought positive changes to the East in recent decades. While the East seeks to integrate the strengths of the West, the West remains stagnant, refusing to learn from the East. It believes that, based on its past success, its way is the only right way. Instead of addressing its deep-seated ideological and structural flaws, it has doubled down on neoliberal policies. The West spends vast resources on media propogandas, NGOs, military, cognitive, trade, technological and financial warfares to defend its system and impose its ideologies on the rest of the world, which is unsurprising given that capitalism has a vested interest in sustaining these ideologies—without them, plutocracy risks losing its legitimacy (see Democracy vs. Plutocracy).

However, the balance of power has shifted. While the pluralistic West once held certain advantages over the monistic East, the East—having integrated Western strengths—is rapidly catching up and, in many respects, surpassing its counterpart. Individuality and sociality are two facets of human nature that must be balanced for the well-being of mankind and society as a whole. Neither authoritarianism, which suppresses individual freedom, nor individualism, which denies humanity's shared destiny, coexistence, and interdependence, can create a cohesive society. Successful society thrives on fraternity, solidarity, cooperation, and the willingness of its people to prioritize collective interests over personal ones and work together as a team. This is how families function (see Tango and Family Values). This is how tango is danced. This is how China is growing strong. And this is how America can regain its strength.

Despite the pervasive influence of individualism, tango offers a powerful alternative perspective. It reminds us that we are not isolated beings but members of an interconnected human family. Through its principles of love, cooperation, and mutual accommodation, tango reveals that true progress comes not from competition, but from collaboration—a lesson that extends far beyond the dance floor. Tango confirms that win-win cooperation and sharing are the true foundations of a better world (see Philosophies that Separate Two Worlds).

October 28, 2016

Meeting in the Middle

For many, life is good. For many others, it is not. We all live in our own reality, shaped by unique experiences and perceptions. These differing perspectives lead us to adopt opposing positions—supporters versus opponents, liberals versus conservatives, reformers versus traditionalists, and so on. Yet, as Guy de Maupassant wrote in his 1883 novel A Woman’s Life, “Life is never as good or as bad as one thinks.”

René Descartes famously declared, “I think, therefore I am” (Discourse on the Method). Human cognition is shaped by personal experiences and, as a result, tends to be partial and biased. In actuality, truth often lies somewhere between opposing views. This is why Confucius advocated for the doctrine of the mean—meeting in the middle—a principle of balance and moderation. Impartiality, avoiding extremes and seeking common ground, he believed, are the mark of a true gentleman (see Understanding China: Geography, Confucianism, and Chinese-Style Modernization).

Meeting in the middle is not only a method of thinking or an approach to life; it is also a civilized way to resolve conflicts. When opposing parties insist on their own terms, they inevitably reach a stalemate. But if both are willing to meet halfway, division gives way to dialogue. Compromise may not fully satisfy either party, but it creates a shared foundation for progress. This is, in fact, how nature itself evolves. The black tulip, as described by Alexandre Dumas in his 1850 novel The Black Tulip, did not emerge from its parent plants overnight but through generations of adaptation and refinement—a process of compromise.

Politicians often seek sweeping, once-and-for-all solutions, but real progress is gradual. Every compromise, however small, is a step forward. While no one may get everything they want, everyone benefits when we move forward together—by meeting in the middle.

What results can be something far greater. As Aristotle said, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” When individuals unite, they create outcomes far beyond their isolated contributions. A single stick breaks easily, but a bundle bound together is nearly unbreakable. In logical terms, the whole is a sufficient condition for its parts—but not the other way around. What benefits society as a whole benefits each individual; what benefits only the individual does not necessarily benefit society.

Individualism as an ideology is fundamentally flawed and as a political theory is anti-democratic. It aligns with the law of the jungle rather than the ideals of democracy (see Tango and Individualism). Those who insist solely on their own way, ignoring the needs of others, act not as citizens of a democracy but as autocrats. A democracy made up of such individuals cannot endure, as evidenced by the growing polarization, obstinacy, extremism, hostility, aggression, lack of restraint, uncooperativeness, and lawlessness in American society.

If we still hold that “all men are created equal” as a self-evident truth, if we still believe that a united and harmonious society serves the best interest of all, if we recognize our interdependence and the need for each other, and if we wish not to be disregarded by others—then we must consider others and not insist on having our own way.

Democracy is a government of the people, by the people, and for the people—not for the most forceful individuals. It relies on cooperation, not antagonism. It seeks balance, harmony, and the well-being of all, not the self-interest of a few. Democracy embodies the Golden Mean, not the law of the jungle. It requires that we resolve conflict through compromise, not through power or force. A democracy must educate its people on its principles.

If we truly believe in these democratic ideals, then meeting in the middle is not only sensible and civil—it is essential. It is the path of democracy—and the spirit of tango. Sadly, at present, we seem to be struggling—both in our politics and in our dance.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)